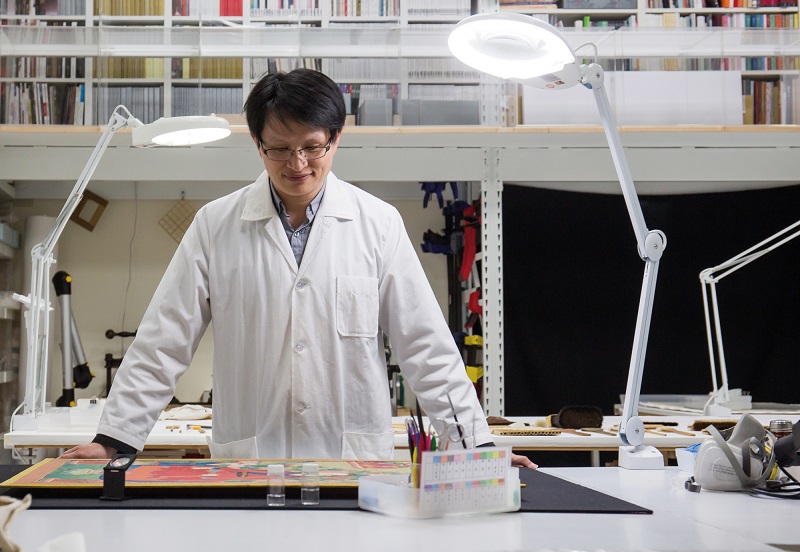

Fan Ting-fu, an oriental art conservator. (photo by Lin Min-hsuan)

SJ Art and Conservation’s Guandu, Taipei workshop exudes quiet, its calming atmosphere reinforced by its white interior and by the gentle movements and whispers of staff members, who are busily restoring precious cultural artifacts.

The way that Fan Ting-fu, SJ’s owner and chief conservator, gushes (quietly) about his work, you might mistake him for a kid gloriously intoxicated by the arts. But once you observe the great care with which he approaches restoration, it’s easy to see how he became the first Taiwanese conservator to work at the British Museum.

SJ Art and Conservation owner Fan Ting-fu was a modern ink painter in university before his interest in how art is displayed led him to zhuangbiao, the traditional art of mounting paintings and calligraphy on rice paper and fabric. His study of zhuangbiao also taught him a great deal about restoration, introducing him to what has become a career in conservation.

|

|

Adjusting one’s outlook

“I began studying zhuangbiao to further my own art,” admits Fan.

Fan explains that when artists finish a work, they usually hand it over to craftsmen for mounting. But he was seeking greater creative freedom: he wanted to control the presentation of his works as well as their content. He therefore began studying zhuangbiao, which led him on to restoration.

After graduating from university, Fan made his formal entry into the restoration field by enrolling in Taiwan’s first academic program aimed at training professional conservators, the Tainan National College of the Arts’ graduate program in the conservation of cultural relics. “I loved learning about restoration and traditional zhuangbiao,” says Fan. “There were so many details to consider, so much to learn about materials and techniques. I didn’t think about that stuff when I was an artist.” But the amount of time-consuming work that goes into restoring cultural artifacts, whether it be removing dust, patching holes, or retouching colors, makes the field seem less than ideal for someone who loves the outdoors as much as Fan.

Moreover, restoration isn’t creation. In fact, it requires artists to repress their desire to create. Fan explains using color touch-ups as an example. The restoration principle of “perceptibility” requires that interventions made in the restoration of a work be clearly distinguishable from the original work, so when a conservator must retouch a spot, the color used should only approximate that of the original. All of the planning and details are frustrating to artists passionate about unconstrained creativity, and Fan admits that it took him more than two years to adjust his attitude enough to be comfortable doing restorations.

|

|

New ideas

While most discussions of restoration today are based on the traditions and practices of Western museums, Fan notes that East Asian painting and calligraphy have their own system, one shaped long ago by the techniques of zhuangbiao.

Fan says: “China has had zhuangbiao restorations all along, but their goal is to restore things to a functional condition, whereas the idea in modern restoration is to preserve the physical condition of the item while also preserving its historical background, aesthetic value, and even its original existential value and perspective.”

Modern conservation and restoration require conservators to have knowledge of a variety of fields, including history, fine arts, art history and chemistry. Conservators must also adhere to the principals of “reversibility” (all added materials and techniques must be removable to facilitate the return of the item to its condition prior to restoration), “perceptibility” (interventions must harmonize with the original, but must also be distinguishable from it), “authenticity,” and “minimal intervention.”

Modern conservation strongly emphasizes surveying records and developing a restoration plan before starting work. When a conservator agrees to take on a conservation‡restoration project, he or she begins by writing up the results of a technical examination of the object. Fan says this resembles “diagnostic data.” The conservator also tests a variety of solvents before drafting an individualized conservation‡restoration plan.

|

|

Clean, unmount, repair, retouch

What’s involved in the restoration of calligraphy and painting? Conservators first study the mounting. Fan says: “Zhuangbiao is literally a process of ‘dressing up’ and ‘decorating,’ meaning that you first mount the work and then decorate.” So restoring a painting requires removing all the accessories, returning the work to its original naked state. Conservators first clean off any dust or stains, then remove the artwork from its mounting, repair any damage, and fill in any color defects with a similar background color. The complex process is abbreviated in the short phrase: “clean, demount, repair, retouch.”

The zhuangbiao restoration tradition has changed little in the last thousand years. But the current generation of conservators has been bringing in new ideas from Western restoration, and trying to implement them in a way that accounts for the uniqueness of Asian painting and calligraphy. For example, the idea behind the principle of perceptibility is that it enables conservators to easily distinguish between the original work and later interventions when carrying out future conservation work, without impairing the aesthetic value of the original. When restoring oil paintings and murals, the Western tradition is to use fine lines to retouch the color. When viewed from a distance, the retouches are difficult to distinguish, but they are easily perceptible when seen up close. But this technique isn’t necessarily feasible when working on Asian painting and calligraphy. Fan says that such works are usually displayed near the viewer. If Western methods of retouching were used, the lines would be too readily apparent. Taiwanese and Japanese conservators have therefore adapted the method to local needs: retouching damaged colors in a similar but not identical color, and refraining from redrawing lines over the retouched areas.

|

|

Cultural interpretation

After finishing graduate school, Fan took an internship at the Shanghai Museum. He went on to work in the art mounting office of the Department of Painting and Calligraphy at the National Palace Museum in Taipei and in the British Museum’s Hirayama Studio, which specializes in the conservation of Asian pictorial art. Fan says that his training in Shanghai resembled an apprenticeship and made him appreciate that zhuangbiao restoration is more than simply a craft, that a whole culture underlies its “clean, demount, repair, retouch” process. “Being a conservator means that you follow in the footsteps of the master with whom you trained.” To Fan, this makes zhuangbiao restoration not just a set of techniques, but the collective cultural memory of a group of people, one that the conservator is obliged to absorb and pass on.

Fan’s time at the British Museum provided him with a completely different view on conservation‡restoration. The people working there came from a variety of nations, cultures and fields, and offered opinions on restoration rooted in those different perspectives. There, he came to view conservation as not just a material restoration, but as a process that is also affected by how government cultural policies interpret cultural relics. Fan says that restoration is itself a kind of cultural interpretation, and as such doesn’t provide cut-and-dried answers. Managing a reasonable restoration involves discussion and debate on a variety of issues, including the objectives of the conservation project and the techniques available.

|

|

Fan believes that Taiwan’s painting and calligraphy restoration techniques are distinctive in the international arena, and hopes that his participation in conferences of global organizations such as the International Institute for the Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works (IIC) and the American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works (AIC) will give Taiwan more of a voice in the international community. Here in Taiwan, he uses his SJ Art and Conservation business to bring museum-caliber restoration services to the general public and raise awareness of the value and significance of conservation and restoration.

While Fan would love to go back to making his own art, he argues that restoration requires its own kind of creativity. Every restoration project is unique, presenting challenges and undertaken for purposes that resist rote answers. Fan may no longer be a painter, but he and his fellow conservators have been transformed by the demands of their field into “action artists” who, through the process of restoration, forge works of “action art.”