New Southbound Policy Portal

Lík-sú Tsiam-tsílâng 1, 2015–2016 (courtesy of Hou I-ting)

Hou I-ting has long been concerned about the “politics of the body”—how images of the body are shaped and molded. Whether this molding occurs in mass culture, or in the history of art, or in the politics of women’s bodies, or in the ways that global production chains employ workers’ bodies, she asks questions about familiar images and then proceeds to reveal the “shaping mechanisms” involved.

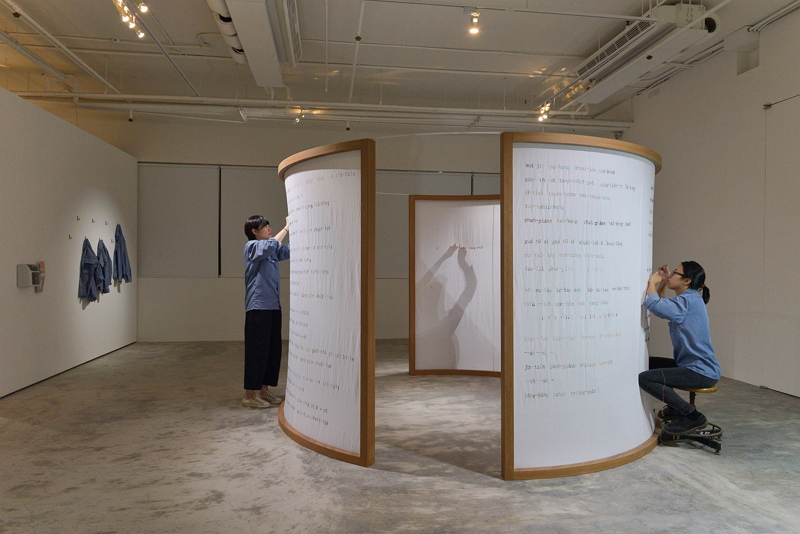

Sewing Fields venue, 2015

Sewing Fields venue, 2015

Hou I-ting’s creative focus was originally on performance art, in which her own body would engage in various kinds of performances and be recorded in images. For instance, in Usurper, to convey the absurdity of trying to meet society’s body ideals, she mixed and matched her own body parts with those of great beauties or female celebrities, or she adopted the poses of cartoon characters and projected images of them onto her own body. In Complexing Body, she took selfies at traditional markets, and then added embroidery and classic elements from Western art history, thus juxtaposing—in all their contradictory glory—elegance (the history of Western art) with crudeness (traditional Taiwanese markets).

Sewing Fields venue, 2015

Sewing Fields venue, 2015

In the previously mentioned works of her early period, she mostly used her own body as her creative medium. Yet over time her focus has turned from her own body toward the various behind-the-scenes mechanisms that are manipulating bodies. If her earlier work mainly had a focus on “the performance of the visible body,” then her more recent work could be described as focusing on “the invisible body.”

In her 2015 show Sewing Fields, her “embroidering actions” are no longer hidden as they are in Complexing Body. Rather, the exhibition spotlights the embroidery process, which is usually overlooked by most people, and features workers who punch in with timecards at the start and finish of work. In the past we would have only seen the finished product as a work of art, but here Hou uses this exhibition of her work to revisit “the process of how a work is created,” before touching upon the labor issues involved in the mechanisms of the arts’ creation. The labor involved in creating art formerly was hidden in the product itself, but Hou has used “on site” embroidery and punch cards to offer an “institutional critique” of the hidden mechanisms endemic to these types of exhibitions.

Lík-sú Tsiam-tsílâng 2, 2015–2016

Sewing Fields venue, 2015

It’s worth mentioning that in contrast to her earlier work, where the artist herself took center stage, in Sewing Fields Hou I-ting does not take the leading role of laborer within the work. Instead, there are also many non-artist laborers who work at the exhibition venue, sewing. This is a form of “de-authorship.” In the series Lík-sú Tsiam-tsílâng, old photos of girls’ schools in Taiwan have been reappropriated. The works look back at history to explore the idea of “collective labor.” The old photos Hou selected mostly capture moments of girls at school collectively practicing the “feminine arts,” where groups of them are engaged in sewing, embroidery, or flower arranging. That past collective work also echoes the current collective work being done in the gallery. Importantly, there is development from the individual’s own body to the politics of the collective. She has left behind the personal experiences of an “author” to move toward “images of the group at labor,” and these group images also blend the labor of the past and the present.

Lík-sú Tsiam-tsílâng 7, 2017

Lík-sú Tsiam-tsílâng 5, 2017

With regard to time, apart from the linear time embodied by the clock punching of the labor performers, Lík-sú Tsiam-tsílâng also stitches together a continuum between past and present through the poses of embroiderers. This process of sewing connects those students of the past with the labor performers on site. Precisely in the mixing of past and present, it causes these women whose bodies seem to have been solidified by photography and education to regain their subjectivity via their “looking back into the lens” and “acts of sewing.” These students at a girls’ school are more than simply objects being watched (or being educated). Rather, in the instant of a mutual gaze between the past and the present, they display a new sense of being active subjects. By looking back at the camera, they resist the stiffness of a one-way gaze.

Lík-sú Tsiam-tsílâng 6, 2017

In short, Hou, via a dynamic dialectical process, takes images frozen in the past and gives them new life, with living, breathing bodies. And these bodies, in contrast to the concrete physicality of her own body as the medium of her early work, are more virtual, historical and political. Meanwhile, they prompt us to consider how our bodies have been molded by historical conditions and to summon new possibilities for collective bodies.