New Southbound Policy Portal

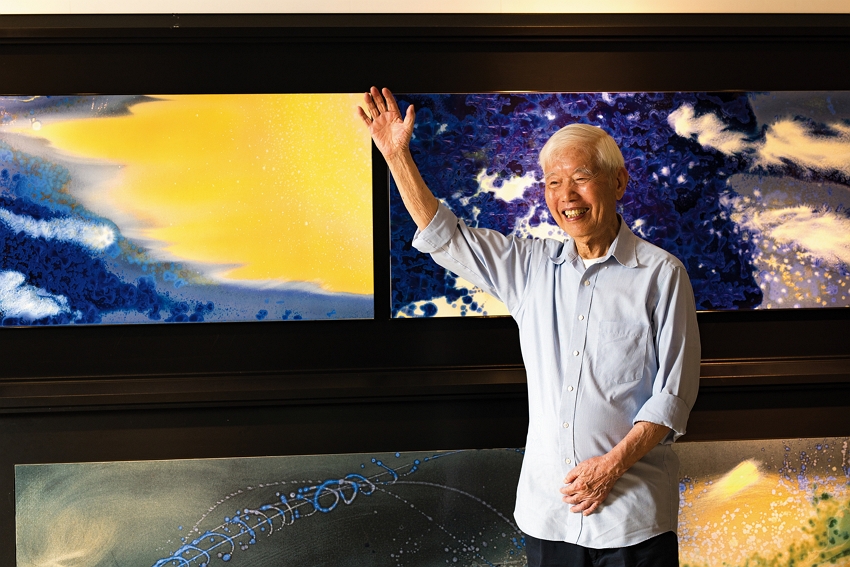

Even in his twilight years, Sun Chao finds pleasure in endless creation of porcelain panel paintings. (photo by Chuang Kung-ju)

Creating unforeseeable, fantastical works of art via kiln firing—this is Sun Chao’s great accomplishment. Recipient of a National Award for Arts in 1987 and a National Craft Achievement Award in 2018, he has devoted his life to perfecting the art of “crystalline glaze,” and thereby established his reputation worldwide. From conventional ware to large painted porcelain panels, he has generated countless works over a period of 60 years. But it was during a trip to France in 2000 that he experienced an epiphany that led him to adopt a sublime methodology, based upon a completely new concept, that inspired him to create objets d’art of unparalleled beauty.

Even at the advanced age of 90 years, Sun Chao maintains a passionate creative ability, constantly seeking innovation and change in the pursuit of excellence. He is the first Taiwan-based artisan to pioneer “crystalline glaze” ceramics. He put down on paper his experience accumulated during three decades of using crystalline glazes for the publication of his book Born by Fire (2011). It explains the formula for such glazes and the firing process in detail, selflessly providing a shortcut for those who wish to follow in his footsteps, and setting an example for generosity of spirit in transmitting his techniques.

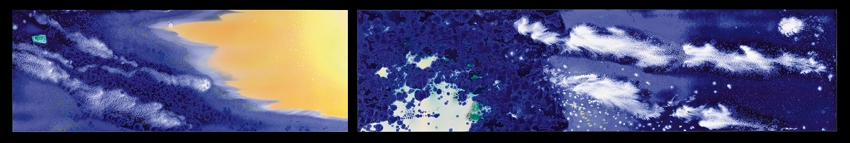

Starlight Yields to Dawn: Via various glaze formulas and flow techniques, the artist created an ethereal ambience for this work, inspired by a Tang-era poem.

“Fire rewrote the destiny of my entire life,” asserts Sun. As a treasured elder grandson born 1929 into a well-to-do family based in Xuzhou in mainland China’s Jiangsu Province, he could not have foreseen that his privileged existence would be turned upside down by war.

When just eight years old, he was separated from his family and survived by begging. Two years of wandering took him from Jiangsu to Hefei in Anhui Province.

His earlier strict upbringing had nurtured a deep-rooted sense of self-discipline. “I always kept my only set of clothing clean and tidy,” he recounts. He withstood the torments of that time, unwilling to contravene the teachings of his paternal grandmother. “Each person must take responsibility for himself.”

It was not until he reached 11 years of age, while still begging for a living, that Sun Chao was taken in and raised by a country gentleman. His adoptive father, who happened to be dining in a restaurant, felt pity for the boy with delicate features, and took him home. “My biggest regret is that I had no chance to study,” says Sun.

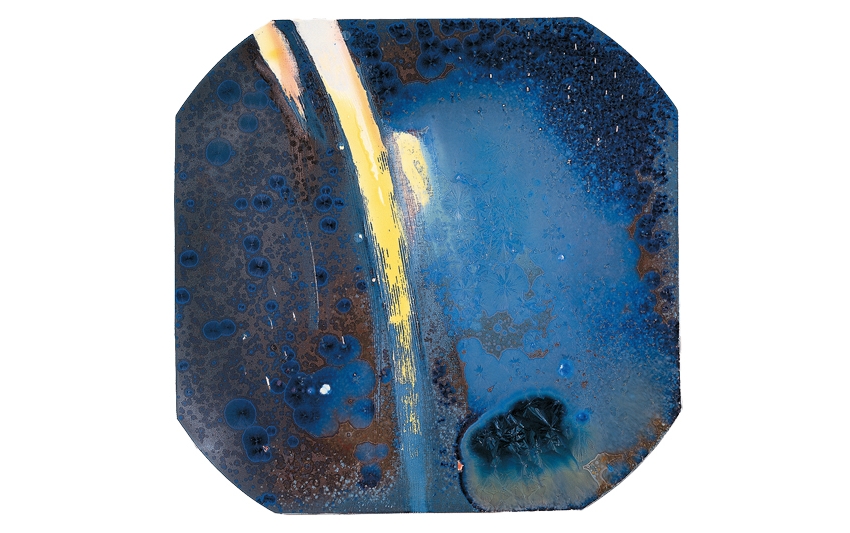

The Galaxy: Crystalline glaze creates a profound and distant vision of black holes and shooting stars.

Having retreated to Taiwan as a soldier with the Chinese Youth Army in 1949, Sun was reassigned to an armored unit. He was once again tempered in battle when mainland forces showered the island of Kinmen with shells during the Second Taiwan Strait Crisis from August to September 1958. Meanwhile, in his bunker Sun casually began trying his hand at drawing. “My sketching skills were honed by copying pictures from Youth Warrior Daily.”

After returning to civilian life, thanks to his self-taught grounding in painting—and despite being 36 years old already—his hopes were fulfilled when he was accepted at the National Taiwan Academy of Arts, where he studied sculpture. One year after graduation, he began working at the National Palace Museum in Taipei.

“At that time, no one there had any experience of firing pottery in a kiln,” he recounts. Tasked with the conservation of porcelain and jade articles, in order to employ scientific data to accurately assess the era and location of their origins, as well as the authenticity of these treasures, Sun acquired a strong interest in the many variations in glazes. Although aware of the potential dangers, he continued experimenting with firing methods.

Sun Down: The heavy crystalline glaze mimics the dazzling beauty of flowers in full bloom.

“One day there was a bang and flames came shooting out from the kiln. My eyebrows and hair were singed,” says Sun, smiling as he strokes his bushy silver eyebrows. “Luckily, my eyes weren’t injured.”

“Firing is a technology apart.” Sun Chao came to realize that the most critical element for the glaze when firing pottery is heat control. “The art of ceramics is the art of fire,” he asserts. Due to his long-term efforts to closely observe changes inside the kiln, he suffered carbon monoxide poisoning several times. “I had many close brushes with death!” he says.

Secrets of glaze lie in the firing“Love is about giving, not possessing,” observes Sun. Obsessed with his research and so poor that he could hardly support himself, Sun didn’t contemplate marriage until he neared 50.

“When we got married, Guan Zheng was an assistant professor at National Taiwan University and had several part-time jobs on the side as well, so her income was much higher than mine. We agreed she’d handle business outside, while I managed the household,” he quips. But just two days into their marriage, his bride banned him from setting foot in the kitchen; she urged him to devote his energies to research instead. After he retired from his post at the museum, Sun commenced his career in the ceramic arts.

Sun Chao has electric kilns built to his own designs, paying particular attention to uniform temperatures and to inclination angles. (photo by Chuang Kung-ju)

“As soon as we arrived here, I felt it was very suitable,” says Sun. Here in Sanzhi, then a sparsely populated, tranquil and secluded township, Sun set up his Tianxin Kiln. “At the time, I was frankly penniless.” In order to earn a living, he made statues of bodhisattvas by day, and researched ceramics at night, burning the midnight oil in search of a breakthrough.

“I tried using a single raw material—iron oxide—and it was a success.” Gifted with an extraordinary sensitivity towards glaze coloring, Sun’s perfect beginning had paid off smoothly. “In fact, the mystery lies in the chemistry.” Each work of art represents the crystallization of painstaking care, and Sun looks adoringly at the first piece he successfully fired with crystalline glaze as if it were a newborn baby. The crystal patterns in the glossy, translucent glaze suggest brightly blossoming flowers that follow the curved shape of the vase. Though somewhat faded due to the passing years, the work retains a fresh and captivating air.

“This is the first large porcelain painting I created after I returned from France,” he says, turning to another work. The shimmering glaze, as if injected with life itself, possesses an aesthetic force that transcends the cultures of East and West, like a liqueur that grows more fragrant with aging.

A perfectionist, Sun Chao takes a hammer to works that fall short of his ideal. His wife Wei Tong-jia cleverly collects the discarded crystal shards and gives them a new life as jewelry. (photo by Chuang Kung-ju)

Ceramic creation is not just a matter of aesthetics, it is also about precision craftsmanship. “You must be capable of a style that is free and easy, yet also meticulous.” Sun Chao first tried his hand at traditional Chinese pottery, both colored and black, and then experimented with crystalline glaze until he came up with his own dazzling style.

“My ambitions grew ever bolder, and the kilns available at the time no longer satisfied me,” admits Sun. He gave full play to one of his special qualities—the rational thought process of an engineer—and drafted his own designs, which he then commissioned others to realize.

“In fact, I actually allow the kiln to create in my stead.” He tilts the kiln, letting the glaze flow as it will, in order to cast its own spell. “I spray a thick coating in some places, and thinner in others. This creates different effects.” Sun is profoundly sensitive to the composition of the glaze, and a master of the precision required in a medium where the slightest imbalance will result in failure.

“Glaze is a remarkable thing. It flows according to your thoughts.” He applies a uniquely spontaneous methodology that generates boundless artistic tension amidst a harmonious mix of pale and strong tints and cloud-like effects.

Evergreen Portrait of Flowers: Sun Chao tweaked his glaze recipe to produce a unique kaleidoscopic effect in this work.

“The glazing process is very labor-intensive and must not be interrupted.” Heavy spray gun in hand, one must remain in place for one to two hours before the stand, and all the decorations must be completed in one session. Amid this grey chaos, all the blueprints are concealed within Sun’s mind; he relies on his eagle-sharp vision to apply each coat precisely.

The most wondrous thing about crystalline glazes is that even when all conditions appear identical, there are subtle differences that cannot be controlled, and they may lead to utterly different results. Those unpredictable variations inside the kiln, often elusive, can trigger delight or failure.

“His works can be viewed from a distance or up close.” The appreciative eyes of metalworking artist Wei Tong-jia, Sun’s second wife, can always find the beauty in his works. When she nimbly extracted the beautiful crystals out of the finished glaze of pieces he had smashed due to imperfections and integrated them into her own delicate works, Sun Chao was frankly amazed. “How come my own failed works, when placed into your hands, become so lovely?”

Easy-going yet detail-oriented Wei Tong-jia always regards Sun with eyes full of admiring reverence, and accepts everything about him with bountiful love. “I am very content now,” Sun says. After more than a decade that he spent painfully mourning the loss of his first wife, Sun and Wei are in harmony with each other, and very much in love.

Inspired by a retrospective exhibition of František Kupka’s works that he viewed at the City of Paris Museum of Modern Art in 1990, Sun Chao began to experiment with fresh techniques after he returned to Taiwan.

“Don’t become entangled in errors of the past. Look ahead, and treat mistakes as a lesson to be learnt.” This advice from family elders has influenced Sun’s entire life. One must not bow to fate or allow failure to compromise one’s ideals; a way out can always be found.

Sun Chao, still hale and hearty at 90, believes that age is merely a state of mind. Fear, disappointment, and lack of self-confidence are the real reasons for aging. “Age wrinkles the skin, but abandoning one’s ideals wrinkles the soul.”

Last year, he won a National Craft Achievement Award. Sun Chao uses glaze paintings to annotate the art of living, and amidst the humanistic glow of his work drifts an air of thought-provoking poetry. “Every era has its own form of representation,” he says. As expressed in his “Sky” series, which features vast star-filled vistas like the desert sky at night, the broad vision of the mind appears to return to the genesis of mankind.

The kiln resembles a womb in which the fusion of sperm and egg is tempered by fire, engendering an unforeseeable miracle that conveys human emotion and poetic imagery of truth, goodness and beauty. This is the joyful life of Sun Chao, and it is also the eternal life of crystalline glaze.