New Southbound Policy Portal

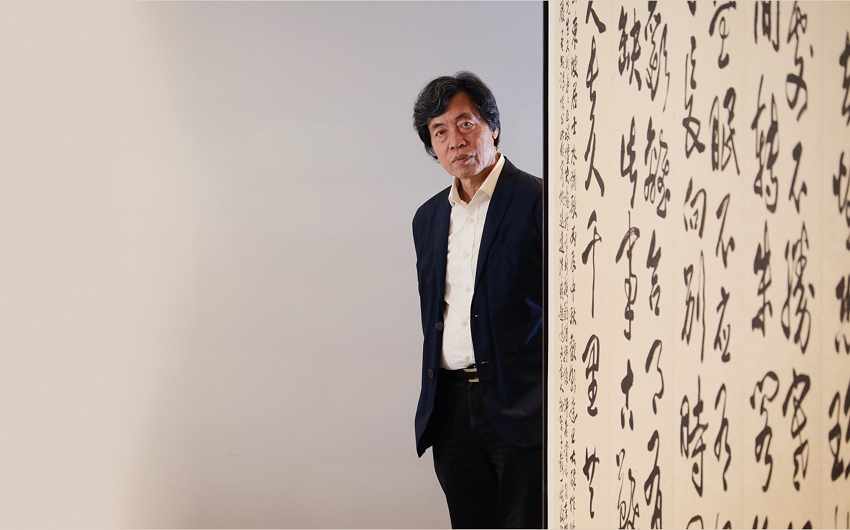

Throughout his days Chu Chen-nan has sought to ascend the artistic mountaintop, and has tried to fill his life with color. (photo by Jimmy Lin)

It is only after leaving home that we gradually understand what homesickness means.

In 1996 calligrapher Chu Chen-nan was awarded a government scholarship to study in France. When he first arrived at the Cité Internationale des Arts, he looked around and saw only a camp bed and a simple desk. The rigors of actual life compared to the splendor of the capital of fine arts that Chu had imagined left him feeling somewhat at a loss.

Chu Chen-nan’s feelings of loneliness made his period of study in Paris rather painful. One day, in order to call home to his family, Chu crossed the Pont Marie to the Île Saint-Louis and went to the only post office on that small island in the middle of the Seine. As a poor student he had little money, but he inserted several one-franc pieces and after some difficulty the phone call went through, but then it was abruptly cut off. Eyes filling with tears, the solitary Chu walked back over the bridge.

However, the rigors of this lonely journey became a major turning point in Chu Chen-nan’s artistic career. “Culturally speaking, I was bringing a cup of Asian tea to the West, to blend it with coffee and see what I would end up with.” Before going abroad, Chu already had a strong foundation in the techniques of Asian ink-wash painting, but was making a brand new start in taking on the challenge of Western painting. The anguish of this mixing of “tea” with “coffee” during Chu’s isolated student existence overseas became a unique learning experience in his life, which he gradually incorporated into his calligraphy and painting.

In Paris in 2019, Chu wrote out the Daoist classic Dao De Jing, a work of some 5000 Chinese characters, on a scroll 18 meters in length, completing the elegant and graceful calligraphy in long bursts of total concentration. “The Dao is an empty vessel; it is used, but it is not filled up / So deep! It seems to be the source of all things / It blunts the sharpness / Unravels the knots / Softens the glare / Merges with the dust.” Writing Asian philosophy in a foreign land created aesthetic and cultural collisions, and it was with this in mind that Chu created this scroll.

This 18-meter-long calligraphy of Laozi’s Dao De Jing was done in bursts of total concentration. It is the best example of Chu’s writing of Eastern philosophy while in the West. (photo by Jimmy Lin)

Chu Chen-Nan is skilled at both painting and calligraphy, especially semi-cursive script (xingcao), and his works appear in many institutional collections and public spaces in Taiwan. The four neat regular script (weibei) characters on Taipei Main Station and the characters for Taoyuan International Airport and train stations in eastern Taiwan were all produced by Chu. When Tou Chou-seng took up his post as ROC ambassador to the Holy See in 2004, he presented a clerical script (lishu) copy of The Apostles’ Creed by Chu to Pope John-Paul II as a gift, which hangs in the Vatican to this day.

Chu also undertook a cross-disciplinary project with the writer and lyricist Vincent Fang to produce an installation artwork for the departure hall of Terminal 1 at Taoyuan International Airport—an illuminated wall of semi-cursive-script calligraphy entitled On the Way: “We can talk about so many things on the road / There is a place full of hospitality / Taiwan is her name.” This soaring work has delighted countless travelers.

Chu Chen-nan is also a painter of landscapes. His creative achievement has been summarized as follows: “He immerses color palettes of the West with the aesthetics of Chinese ink and brush. He harmonizes calligraphy with painting through his mixtures.” His work manifests the nature of Asian ink-wash painting while also possessing the luster of a modern artistic vocabulary.

In his Winter of New York, painted in that city, Chu depicts a group of people skating on a winter’s day. Amidst the bare branches in black and white, a woman walks gracefully toward the artist. “I painted this woman to be 172 centimeters tall, aged between 30 and 40, wearing a Chanel jacket, and walking with elegance.”

Aiming highWhen Chu Chen-nan went to study under the famous calligrapher Shie Tzung-an, Shie said to him: “Chen-nan! If you don’t drink alcohol, you needn’t bother doing semi-cursive calligraphy.” Thereafter Chu went to class at 11 each morning so that Shie could assess his work. Then he would sit with his teacher drinking, and at noon they would watch the news and talk about the aesthetics of calligraphy. “If you want to pursue a uniquely high status at the top of the mountain, you have to aim high, so I decided to set a tone of aiming high.”

“My personality is rather unconstrained, and I tend not to pay attention to details. That’s why I made a point of studying with Shie Tzung-an, a master of beixue [the study of engraved calligraphy] who was skilled at clerical script, regular script, and seal script [zhuanshu].” Because beixue focuses on exactitude and neatness, Chu deliberately “made trouble for himself” by seeking out the best possible teacher for this school, as a way to temper his own disposition.

Chu Chen-nan comes from a very poor background, and in the 1950s and 1960s Shimen on Taiwan’s north coast was a remote and impoverished place, far from Taipei. In an era when no one had anything, it was tough just to get by day to day. “If you wanted to get through the day, you had to learn to be khiáu [Taiwanese for ‘smart’].” Growing up having to be deferential to others, Chu learned very quickly how to be khiáu. To get some lunch to eat, he would walk to the sea, where he could catch a lot of shrimp to fill his belly. Looking up at the clouds in the sky, he could tell if a typhoon was coming. In the spring he planted out rice seedlings, and in the fall he harvested the crop, while also knowing the tides—Chu could do everything.

“That’s why my approach is natural, one of learning from nature. I see different things from other people in landscapes or in the flow of water.” Chu then effortlessly recites a poem: “The moon hangs in the sky / The wind blows over the water / There is a feeling of clarity and freshness / But few people can sense it.” In painting landscapes, Chu has his own kind of pure-hearted romanticism. “I can take a sheet of paper and a brush and paint freely, because at that time your observations are keener than other people’s, because you are not so insensitive toward nature, not so lacking in understanding.”

Calligrapher Chu Chen-nan believes that spiritually he is a combination of ancient and modern, Chinese and Western. In his works he blends calligraphy with painting, and ink with colors. (photo by Jimmy Lin)

Today Chu’s mind is filled with poetry and book learning, but as a child he had no chance to indulge his brilliance. There are a lot of chores to be done on a farm. Cultivating the land comes before everything else, and every child had to pitch in. Herding ducks in search of food, bringing hens to mate with roosters, “how could you even talk about studying when there was still work to be done around the house? There was no way for that to happen.”

Chu still remembers how as a child he walked through the mountains with a hen under his arm. “When I saw a rooster with a high cockscomb I just threw the hen onto the rooster.” After that the hen started to brood a clutch of eggs, and a week later Chu’s mother opened the door a crack and used a small lightbulb to inspect them. She counted on her fingers, one, two, three, four, five—five eggs were not fertilized, for Chu had not done his work properly. He knew it was time take to his heels, or he would be in for a beating with the bamboo broom.

All glory is fleetingChu, who has always been grateful for others’ help and his own good fortune, has invariably been a generous alumnus to his old university. In Paris, to help a church raise money, he wielded his brush for a foreign audience. And at the time of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, Chu flew to the town of Yamada in Japan’s Iwate Prefecture to use his writing brush to produce name plates for the houses of survivors relocated to prefabricated housing. This kind gesture really touched their hearts.

“I’m sentimental by nature, so I will do more and care more for others. But I’m also more easily unsettled, and have too many hang-ups.” Chu laughs helplessly. It’s distressing that there are so many attachments in life, and he can’t find calm for his creative process. This is the downside of being so sentimental!

In this mortal world, when you possess paramount ability or are greatly successful, there’s a feeling of being alone, like standing on top of a mountain. Though he has not yet reached the mountaintop, Chu Chen-nan has already perceived the transience of fame and fortune. “What’s the point of being trapped by reputation?” With these words, Chu writes a footnote to his bold and generous spirit.