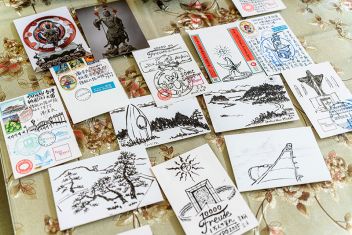

photo by Lin Min-hsuan

According to a report released by the National Central Library in April 2021, the number of new books published in Taiwan has fallen for the third year running and is now at its lowest in 20 years. The printed word no longer seems to be in demand. Where have all the readers gone?

Wondering whether publishing is dead in our digital age, we have interviewed several professionals in the publishing industry.

“Many people say that reading is in decline. I don’t agree. I think we’re actually reading more often than before. It’s just that the carrier of the text, and the experience and form of reading, keep evolving,” says David Weng, cofounder of vocus.cc.

“Contrary to what you might expect, reading has not suffered a decline at all. People spend more time reading now. You can even say they’re reading all the time,” says Evany Chou, editor-in-chief at Openbook.

Patience Chuang, editor-in-chief at Spring Hill Publishing, observes: “It’s not so much that publishing is in decline, but rather that traditional publishers have not come up with new interpretive and marketing strategies to interact with modern readers.”

In recent years, these book-loving professionals, who are devoted to high-quality publications, have been working hard to promote reading. In response to challenges peculiar to our digital age, they hope to forge new opportunities for the traditional publishing industry.

Relying on subscribers

Established in 2018, vocus.cc is a reincarnation of SOSreader, which was committed to serving journalists and facilitating the publication of in-depth reports. While vocus had to invite literary celebrities to write for it at first, many renowned writers have since come on board on their own initiative, and the number of writers who use their services is growing steadily. Now vocus is the largest online writing platform in the Chinese-speaking world. It’s surprising that cofounder David Weng is only 32 years old.

Just like blog hosting platforms, which used to enjoy immense popularity in Taiwan, vocus provides services for writers. Both types of creative platforms host vast quantities of text produced by writers across the world. The difference is that blog hosts derive their incomes from advertising, while vocus, which asks readers to pay for some of its content, operates a “no ads” policy.

This policy originates in the importance Weng attaches to the quality of published text, but it also reflects the specific reasons why vocus was founded. “Our first company, SOSreader, was a venture in new media. But we soon noticed a challenge often faced by the media—that is, the content of your journalism can run counter to the beliefs and opinions of those who place ads on your website.”

If your website attracts large amounts of traffic, you can indeed make money from advertising, but this will impose many limitations on what you can publish. Unwilling to compromise his principles for the sake of profit, Weng sought to establish a different kind of platform for content creators by studying successful international cases, including the US-based Patreon, which is one of the world’s largest membership platforms, and Medium, an online publishing platform specializing in journalistic writing.

Decentralization

In a world where the reading public is increasingly segmented, vocus suits those who write for small audiences. Here writers present their work without having to go through complex editorial and printing processes, while readers are expected to pay only a few hundred NT dollars for access. The content on vocus is not only fresh and up to date but also inexpensive. Writers are given complete creative freedom and can put a price on their own work. If someone has several hundred subscribers, their income will far exceed what they are likely to get from traditional publishing.

“Articles published on vocus often strike us as being somewhat roughhewn but more lively, offering more interesting points of view,” Weng says. In addition to popular subjects such as business, management, technology, and financial analysis, some niche topics—including the sex industry in Thailand, military weaponry, and even how to cope with divorce and adultery—also attract massive numbers of subscribers. “Traditional publishing models have to consider minimum print runs and meet certain fixed costs. Our ‘decentralized’ model, which bypasses production costs, is able to give creative space to many writers who focus on niche, specialized topics,” Weng explains. What vocus seeks to do is precisely to provide a timely platform for a diverse array of voices in modern society.

Staying up to date

Created in 2017, Openbook has already become one of the most representative Chinese-language websites specializing in book reviews. Openbook’s annual book awards have also become an event much revered in the publishing world.

This new media platform has been basking in early success, but it didn’t really start from scratch. The founders—Amy Mo, Lotus Lee, and Evany Chou—are senior professionals in the publishing industry, having served as successive book review editors at the China Times.

Moving from a traditional weekly supplement to a web-based platform that is updated every day or even several times a day, Openbook supplies up-to-the-minute information and interacts more directly with its audience. Unrestricted by column inches, and able to incorporate visual and audio materials, Openbook has succeeded in reaching readers from a wide variety of backgrounds.

Chou further observes that there have been corresponding changes in the kinds of books that are selected for reviews and awards. “The media are becoming more and more diverse, and readers now privilege faster rhythms and styles. They prefer succinctness and read in a fragmentary way. Visual narratives have also become a crucial way to communicate information.”

Accordingly, Openbook embraces not only traditional literature but also children’s books and graphic novels. Openbook’s criteria for its annual awards are also designed to ensure diversity in terms of content and genres, jettisoning the traditional emphasis on serious, canonical tomes.

A leading brand

Openbook entices individual readers by delivering “beneficial and interesting” content, but it also has a more important role to play: helping to nurture a culture of critical thinking essential to every modern democracy.

Amy Mo draws our attention to one of the most authoritative book review platforms in the English-speaking world: The New York Times Book Review, which first appeared in 1896. Its centenary anthology, Books of the Century, “encompasses the history of publishing in the West over the course of its first 100 years, reflecting the evolution of every field, and initiating new trends in intellectual inquiry.”

Openbook isn’t the only platform offering Chinese-language book reviews, but it’s the only brand in Taiwan that introduces new books in a systematic way. It also explores larger book-related issues. For example, in response to the inexorable rise of picture books, Openbook’s editorial team have produced a series of reports on international trends and government strategies, providing advice for artists, writers, and publishers, and inviting senior figures to share their experiences. In this regard, Openbook’s work can be said to constitute a national asset.

For its three enthusiastic founders, not only is Openbook a love letter to books, but it also paves the way for active social engagement.

Finding a consensus

Patience Chuang was previously editor-in-chief at Acropolis, a well-known publishing house focusing on the humanities and social sciences. In 2018 she left the company she had built up from nothing to establish Spring Hill Publishing, naming this new venture after her parents.

Although she still concentrates on the humanities and social sciences, Chuang has a soft spot for imaginative literature. She thinks that people from all backgrounds should be able to find a meeting place in literature.

In a world where seemingly irreconcilable ideologies never cease to clash, literature represents a soft power, reminding us that we all share certain fundamental values. Chuang says: “Whereas the social sciences introduce us to inspiring concepts, we need mutual sympathy to coexist with each other in this world.”

In this spirit, when devising Spring Hill’s four book series Chuang thoughtfully included in one of them a periodical called Springhill Literati, which continues the work of Letter, her previous literary magazine at Acropolis. Literati embodies her hopes for the world.

Socially engaged literary criticism

To explain her conception of literary criticism, Chuang refers to Being Hong Kong, a magazine inaugurated in 2018. Devoted to literature and art, it nevertheless chose to feature Hong Kong business magnate Li Ka-shing in its first issue. Chuang was inspired by this “worldly” approach. “Literary magazines should work harder to cross borders and even discuss politics,” she says.

Fueled by this idea, Chuang has been able to tap into the contacts and resources she amassed during her time at Acropolis. For example, in the first issue of Springhill Literati, her team invited Wu Rwei-ren, an expert on political philosophy who had worked with Chuang, to write about the spirit of early modern Japan through the lens of Japanese writers who committed suicide. They also invited Tsai Chinghua, a writer who holds a PhD in politics, to discuss the Nobel Prize in Literature. In Literati, fiction and non-fiction, imaginative literature and the humanities and social sciences, are no longer separate disciplines. They resonate with and enrich each other.

With the literary marketplace entering a sluggish period, Chuang established her literary magazine at an unpropitious time. But she’s confident and hopeful: “Through in-depth, high-quality criticism, we wish to dig into literary works and the minds of their authors, to interpret literary texts and rediscover their historical contexts. If we can bring criticism to this level, perhaps we can make literary works live longer in our hearts.”

For more pictures, please click 《Catering to Modern Readers: New Reading Trends》