Senior guide Huang Ya-ting encourages first-timers to start by checking out the visitor center. They can then hike the trails with a greater understanding of the park’s ecology.

Kenting National Park, Taiwan’s first national park and its most visited, covers some 32,000 hectares equally split between land and sea. South Penghu Marine National Park is Taiwan’s newest national park. Covering an even larger 35,000 hectares, 99% of which is at sea, it features rare columnar basalt islets as well as rich, pristine coral reef ecosystems.

Established in 2011, Shoushan National Nature Park includes Banpingshan, Guishan, Shoushan, and Qihoushan. Some 300,000 years ago, these four mountains were created from uplifted coral limestone. Each mountain has its own special characteristics: Banpingshan is a great place to see birds of prey; Guishan has hosted a variety of military bases in different eras; Shoushan has the richest ecological resources; and Qihoushan holds coastal ecologies and old forts of historical importance. Close to the city center, the park gives urban residents access to the joys and tranquility of nature without needing to travel long distances.

What’s in a name?

Senior guide Huang Ya-ting, who has been acquainted with the mountain for more than a decade, went to work at the park headquarters not long after its founding. The park’s rich ecologies and history attracted her to study them in depth. She holds to the viewpoint of Seiroku Honda (1866-1952)—the “father of Japan’s parks”—in believing that the composition of Shoushan’s forests reflects the cultural history of its area.

Shoushan lies within the city of Kaohsiung. The plains Aborigines used to call the place where Kaohsiung now stands Takow (their word for the thorny bamboo that grew there). Later, Han Chinese settlers approximated the sound by calling it Tá-káu (Dagou in Mandarin), meaning “beating the dog.” Consequently, Shoushan was originally known as Dagoushan. It wasn’t until the Japanese era that the colonial government found the name Dagou unbecoming and replaced it with the similar-sounding Japanese name Takao, taken from an area in Kyoto, Japan and written with Chinese characters that are pronounced gaoxiong (Kaohsiung) in Mandarin. After Crown Prince Hirohito visited in 1923, the mountain Dagoushan was likewise renamed Shoushan (“long life mountain”) to celebrate the prince’s birthday.

Nevertheless, even today many call it Chaishan (“firewood mountain”) because locals gathered firewood there during the Japanese era. By cutting down the trees, they severely altered the landscape. John Thompson’s 1871 photograph The Entrance to the Port of Takao shows Shoushan denuded of trees. Westerners who had visited Shoushan knew it by still another name: Ape’s Hill. In 1873 the American ornithologist Joseph Beal Steere (1842-1940) noticed some gray monkeys there and conjectured that they had given the mountain this name.

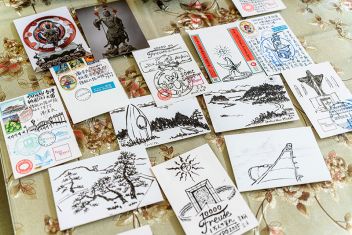

In addition to its rich natural resources, Shoushan National Nature Park also features historical relics that attest to Kaohsiung’s prosperity in the 19th century.

Highly varied from north to south

Over time, more than just the name of the mountain changed. Its woodland vegetation turned from sparse to lush. During the Japanese era, the colonial government made Shoushan and Qihoushan the island’s first protected forest area so as to safeguard their water resources. The government strictly prohibited the felling of trees and planted quick growers such as Formosa acacia (Acacia confusa), Chinese banyan (Ficus microcarpa), whistling pine (Casuarina equisetifolia) and white leadtree (Leucaena leucocephala) to achieve reforestation. In 1925 the government also invited Seiroku Honda to come to Taiwan and develop plans for a Shoushan Memorial Park, which involved the planting of many ornamental tree species in Shoushan’s southern section.

In 1937 war broke out between China and Japan, and Kaohsiung became a fortified command center. Because Shoushan overlooked both Wandan Harbor (now Zuoying Naval Harbor) and Kaohsiung Harbor, it was included in a military control zone. Plans for the park were put on hold.

Huang explains that there is tremendous variation in the Shoushan forest. Because the north side is mostly under military control, native plants predominate and there is greater biodiversity. The central area of the forest mostly consists of pure stands of white leadtree. The southern area, on the other hand, is the main area of Japanese-era afforestation, which disrupted natural ecological development, leading to a reduction in biodiversity. She recommends that visitors enter the forest from the northern trailhead of the summit trail in order to enjoy the richest ecological views.

Garnering international attention

Not long after starting out on the trail, we see Formosan rock macaques (Macaca cyclopis) on some stone steps, playing, scratching themselves, and provocatively jostling each other. Huang reminds everyone not to feed or touch them since several diseases are transmissible between macaques and humans. If a young monkey does jump on you, she advises, don’t panic or shout. Simply squat down slowly beside a tree, and the macaque will return to the branches of its own accord.

Taiwan macaques first received international exposure after the British consul in Taiwan, Robert Swinhoe, sent specimens back the British Museum, which determined that the species was endemic to Taiwan. Likewise, Chinese yam (Dioscorea doryphora) and dye fig (Ficus tinctoria)—both common in Shoushan—also first received international notice after Swinhoe sent specimens to the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew. In Taiwan he collected specimens of more than 200 plant species, over 200 bird species, more than 400 insect species, and many snail species. Thus began the field of natural history in Taiwan.

Another Brit, Augustine Henry (1857-1930), was also an important early figure in the study of Taiwan’s natural history. While he worked as a customs physician in Dagou, he first identified and collected 94 species that are endemic to Taiwan, including Taiwan amorphophallus (Amorphophallus henryi, a.k.a. Henry’s voodoo lily), which is challenging to collect given its short blooming period. It flowers in April or May, emitting a malodorous scent that attracts flies and other insects to help it pollinate.

Walking along the North Shoushan Trail is like a trip through time, as Huang leads us through stories from natural history. Banyan trees, which were already growing here in the Qing Dynasty, employ aerial roots to expand their area and consequently are known as “trees that can walk.” Here too is Naves’ ehretia (Ehretia resinosa), which was collected by the British plant collector Charles Wilford (d. 1893). The chief distinguishing characteristics of the tree are its small white flowers and thick bark. It used to be a major source of firewood for local households. And there is towering thorny bamboo (Bambusa stenostachya), which is what Aborigines originally named the area after. The Makatao tribe used the plant for building stockades to keep out pirates.

Nevertheless, after Shoushan became a nature park, the cutting and trimming of plants was strictly forbidden in order to protect its precious natural resources.

Shoushan’s Formosan rock macaques aren’t scared of people and can be found lounging throughout the park.

Magnificent limestone terrain

Halfway along the North Trail, the landscape on both sides changes from mountain forests to limestone walls. This spot is the famous “Thread of Sky.” When the uplifted coral reef was subjected to pressure from the Shoushan geologic fault, it created a crack in the limestone that over time grew wider, eventually developing into a gorge. Walking ahead a little way and then using ropes to climb the slope, we reach a gully with roughly striated limestone walls.

Nearby, there is the “Dream Curtain,” where the aerial roots of the ornamental princess vine (Cissus verticillata) create a curtain-like effect, filtering the sunlight to produce a mysterious atmosphere. “Still, the princess vine is an exotic plant, so sometimes we need to ‘trim its hair’ to keep it in its place.” Huang explains that in trying to strike a balance between ecological conservation and tourism, the park administration has elected to allow the vine to grow within a certain defined area, giving visitors a chance to see this unusual sight.

The highest point on the trail is the Yazuo Pavilion. Visitors get beautiful views of the Taiwan Strait there and may catch glimpses of Formosan macaques at play. Some hikers also regularly lug up 20-kilo containers of water, so that all visitors may quench their thirst as they take a breather.

Several 19th-century Western naturalists, the 20th-century “father of Japan’s parks,” and present-day eco guides have all helped to reveal the beauty of Shoushan, playing their respective parts with passion and expertise. As Huang explains in her master’s thesis, on the history of Shoushan’s changing vegetation, the visual richness of Shoushan has been shaped both by natural forces and by the “cultural forces” applied by people of different eras. The beauty of Shoushan lies not just in its ecologies but also in its stories, written over two centuries by unsung heroes.

Safety Tips for Visitors:

1. To avoid contracting scrub typhus, which is transmitted by chiggers and can cause a high fever and even death if not treated promptly, wear long sleeves and long pants, apply mosquito repellent, and avoid touching plants while hiking.

2. It is easy to lose your way on small mountain tracks and stray into military areas, so stay on the boardwalks as much as possible.

3. To keep from getting lost, take a photo of the map at the trailhead. If you do get lost, don’t panic.

Just find your coordinates by zooming in on Google Maps, then call 112 to ask for help.

4. Pack food carefully inside your backpack to avoid attracting the attention of macaques.

Feeding macaques and stray dogs is strictly prohibited.

5. It is forbidden to enter the limestone caves without prior authorization.

6. To prevent the transmission of diseases between animals and humans, it is forbidden to bring pets onto the mountain.

For more pictures, please click 《Kaohsiung’s Eco-Paradise—Shoushan National Nature Park》