This caisson ceiling is made entirely of bucket arches linked by crafted wood joints without a single nail. Such ceilings are a major test of a carpenter’s skill.

Tianhou (“Empress of Heaven”) temples, dedicated to the goddess Mazu, are centers for all kinds of traditional craftsmanship. In this article we visit three masters of temple crafts: carpenter Liu Shengren; Guo Chunfu, a maker of headgear for deities’ statues; and embroideress Zhang Lijuan. By looking at their decades of consummate work, we can appreciate their professionalism and admire the beauty of Taiwanese crafts.

On entering the main hall of Bengang Tianhou Temple in Chiayi, we look up and see directly above us a magnificent octagonal caisson ceiling. “Temples with caisson ceilings are the most beautiful,” says master carpenter and joiner Liu Shengren, our guide for this visit. The bucket arches (dougong) that rise layer upon layer are all connected by crafted wood joints, without the use of a single nail. However, not all temples have decorative ceilings of this kind, for a caisson ceiling is not only symbolic of a temple’s size, it also represents the skill of the master joiner who constructed it.

Liu Shengren, who was born into a well-known family of carpenters, sees the restoration of historic buildings as his life’s mission.

Generations of carpenters

Liu Shengren was born into a well-known family of carpenters in Xingang, Chiayi County. It was Liu’s great-grandfather, assisted by Liu’s grandfather and great-uncle, who carried out the restoration of Bengang Shuixian Temple, a national monument, after World War II. For Liu, the carpentry in the temples they have worked on is a symbol of the family’s honor.

After graduating from junior high school, Liu was apprenticed to a cabinet maker. During his military service he was put in charge of a woodworking unit and continued to gain experience. After he was discharged, Liu studied structural carpentry under his uncle Liu Honglin, with whom he worked on the construction of Bengang Tianhou Temple and Santiaolun Haiqing Temple, as well as doing restoration work on a number of traditional Taiwanese and Japanese-style structures.

Liu, for whom carpentry has been a lifetime vocation, has always remembered these words of Liu Honglin’s: “Once you take on a project, you must finish it, even if you lose money along the way.” For example, during his first big project after going into business for himself—the restoration of Zhongshan Hall at Pingtung Tobacco Factory—the construction company went out of business and could not pay him, but he insisted on finishing the job, paying his workers out of his own pocket. This conscientious and persevering attitude has enabled Liu to continually gain experience, eventually becoming the first person in Taiwan to be recognized by the Ministry of Culture as a master craftsman in three fields: both structural carpentry and joinery in traditional Chinese-style architecture, and structural carpentry in Japanese-style architecture.

A lover of temple architecture

Liu has taken part in restoration projects at many historic sites, including Tainan’s Grand Mazu Temple and the old Chiayi Prison, but he says his favorite type of architecture is still traditional temple buildings. This is because, in contrast to the measured style of Japanese colonial architecture, Chinese-style temples are characterized by their rich craftsmanship. For example, the main framework (dongjia) of beams and columns that supports a temple’s main hall has a series of two or more supplementary crossbeams above the main crossbeams, below the high roof. Short vertical struts, called guatong (“gourd posts”) are placed between these crossbeams to consolidate the structure, and are carved in the shape of pumpkins, papayas and other fruit with large numbers of seeds, symbolizing the auspicious wish for families to be blessed with many offspring.

Liu says that because wood is a living, natural material, it creates a more mellow feeling and becomes more attractive the more one looks at it. This is why people feel at ease when they walk into a Mazu temple. For Liu, restoring temples and historic sites is like doing meritorious deeds—he doesn’t worry about profit and loss, because what is more important is to preserve the history and culture of monuments and the warmth of their wood.

Guo Chunfu has been using his metalworking skills to make deities’ headgear for nearly 60 years. He is one the few craftsmen who can make such headgear out of various materials including silver, bronze, and paper.

Sixty years of deities’ headgear

It is 2:30 a.m, and in the basement of a private home in Tainan’s South District, the flame of a soldering torch plays over strands of fine silver wire. Guo Chunfu, working with a magnifying glass, carefully shapes the wires according to a design he drew himself, soldering them onto a silver plate point by point. Each and every component of the different types of deities’ headgear that Guo makes is the result of complex work processes that he repeats day after day at his workbench as he gradually creates these items. Working entirely by hand, it takes him at least several months, and sometimes over a year, to complete each piece. This is how the crowns of the Mazu at Lu’ermen’s Tianhou Temple and the Second and Third Mazu at Tainan’s Grand Mazu Temple came into being.

Born in 1950 in Tainan’s Yancheng Township (now Yancheng District), Guo Chunfu began studying metalworking with his uncle right after he graduated from primary school. At age 17 he went into business for himself. At first he worked for jewelry shops, making ornaments and gold medallions, but occasionally a customer would bring him an item of deity’s headgear and ask him to make a copy.

In 1970 Guo began his military service, and met a master sergeant named Zhong whose family was well known for manufacturing officers’ caps. Zhong taught Guo how to make paper hats, and so laid the groundwork for Guo’s future transition to specializing in making deities’ headgear.

As Taiwan’s economy took off in the 1970s, many citizens who were earning more money than before chose to repay the gods’ benevolence with custom-made headgear. In the 1980s, playing the illegal Dajiale lottery became enormously popular in Taiwan, and demand for custom-made deities’ headdresses outpaced supply. Accordingly Guo intensively studied the patterns of deities’ clothing and headgear, and gradually shifted his focus to hand-crafting such headgear.

Mazu’s unique headgear

Guo relates that every deity has his or her own unique rank, requiring different types of headgear. For example, after Mazu was promoted from Tianfei (“Heavenly Consort”) to Tianhou (“Empress of Heaven”), her headgear also changed. Because there is no fixed pattern for deities’ headgear, each craftsperson must rely on their own knowledge and skill. Guo has always insisted on personally measuring the head size of each deity, because he wants to ensure that the headdress perfectly fits the shape of the statue’s head, as only then will it appear neat and beautiful.

This is why Guo and his wife have ridden all over Taiwan on their motorcycle, and he even paid his own way to fly to Penghu to take measurements. He also insists on delivering the finished product in person and placing it on the deity’s head himself, only considering his work done after meticulously adjusting every detail.

Not just an accomplished craftsman, Guo in fact seems more like an artist. On one Mazu crown which was only 12 centimeters in circumference, Guo included nine dragons and four phoenixes. He even insists on making complex designs on the back of his deities’ headgear, a place that few people even notice. Looking closely at one of Guo’s works, we see that for the body of each openwork dragon he first weaves silver wire strand by strand into a fine mesh, then solders the strands together and places the mesh onto a mold to form it into a cylinder, before finally trimming it into shape. It is truly meticulous precision workmanship.

In 2000, he was commissioned by Tianhou Temple at Lu’ermen in Tainan’s Annan District to make a crown for the Mazu statue in the main hall that would be about 146 centimeters in circumference. “This is probably the biggest deity’s headdress in the entire world,” says Guo confidently.

Lu’ermen’s Tianhou Temple draws many worshipers, and over the years the crown became very dusty from the incense smoke. In 2021 Guo was again commissioned to clean and restore it. He first carefully removed every decorative piece from the crown, and then used a flame torch to restore the crown’s color, after which he soaked it in hydrogen peroxide to loosen the dirt, brushed it clean, electroplated it, sprayed it with a protective film, and finally reattached each of the accessories one by one. Although it is more than 20 years old, the crown still looks like an exquisitely wrought work of art, adding to the dignity and grandeur of the main hall’s Mazu statue.

Seeing Guo’s expression as he attentively gazes at a deity’s headdress, we ask him if there is anything with which he is not satisfied. He replies: “Whenever I complete a headdress, I look to see what I can improve upon. This is the only way to make the next one even better.” He continues to pursue excellence, saying “I will make deities’ headgear until the day I drop, and that last piece will be my finest work.”

Zhang Lijuan has been doing embroidery for over 60 years. In her hands, needle and thread are like artist’s brushes as she produces beautiful clothing for deities’ statues one stitch at a time.

Mastery of needle and thread

Watching the petite master embroideress Zhang Lijuan as she confidently prepares to put the tip of a very fine embroidery thread through the eye of a needle less than a millimeter wide, she has a smile on her face and a look of determination in her eyes as she succeeds at the first try—you would never guess that she is nearly 80. As Zhang tells us about her past and how she first learned embroidery, she works on a piece of deity’s clothing that must be delivered the next day. As she maneuvers the needle through the cloth, it seems like an artist’s brush as she flowingly embroiders gold thread onto the fabric. After a few moments of skillful work, the thread brightly embellishes the flat cloth, showing off the mastery that Zhang has gained over the course of more than 60 years in her craft.

Zhang was apprenticed to an embroidery business when she was 14 years old, learning the art from a master who came from Fuzhou in China. She learned to correctly gauge the force with which to apply her needle, and to handle it with precision, mastering skills from flat embroidery to cotton-raised embroidery to goldwork.

After Zhang had spent several years as an apprentice, the owner of the business moved away and closed down the shop. Customers who liked Zhang’s skillful work encouraged her to go into business for herself. They introduced new customers to her, and as her reputation spread her business flourished. In 1989 Zhang moved her workshop to a corrugated steel structure in the suburbs of Chiayi City, where it remains to this day.

Transforming traditional crafts

As times changed, manpower became increasingly expensive and there was growing competition from inexpensive embroidery from China. Therefore Zhang switched her workforce from doing embroidery entirely by hand to using sewing machines for some elements. Also she began using polystyrene foam for the raised embroidery, which in earlier days was padded with hand-rolled cotton wadding. Zhang says that while polystyrene foam is quick and easy to use, it is less flexible, whereas with cotton wadding one can more finely vary the height of the raised embroidery, giving vitality and energy to the finished product.

Zhang takes out a set of clothing that she hand-embroidered for a Mazu statue, with a dudou (an apron-like bodice covering the chest and belly), outer garment, shawl, and headdress. She says that most deities have only an outer garment and headgear, but Mazu statues must first be dressed with a dudou, then a robe and shawl. The embroidery on the Mazu attire she is showing us was inspired by a motif known as “two dragons flanking a pagoda,” with a raised pagoda embroidered using cotton and gold thread, and a goldwork dragon and carp on each side, as well as phoenixes embroidered on the shawl, making for an exquisitely beautiful work. One can imagine how imposing a Mazu dressed in these clothes would appear.

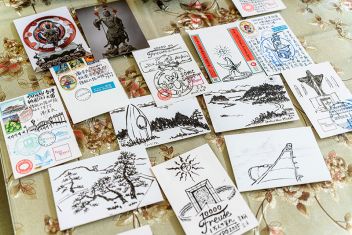

A few years ago the Chiayi City Cultural Affairs Bureau organized a design exhibition for which they invited six master craftspeople and six contemporary designers to work together to create innovative works, in hopes of injecting new life into traditional crafts. For the embroidery work they sought out Zhang Lijuan and the designer Mayi to collaborate on a piece entitled “The Eight Immortals Tour Chiayi City.” Zhang led a team of master embroiderers as they spent several months continually sewing in and tearing out stitches and starting again, until they finally produced a beautiful work featuring local culture and cuisine, including Chiayi Park, fish-head casserole, and chicken with rice. Today this remarkable work is part of the permanent exhibition at Chiayi Municipal Museum, enabling citizens to admire the beauty of Taiwanese craftsmanship up close.

The next time you go to a Mazu temple, besides basking in the dignity and tranquility of the incense-laden ambience, don’t forget to take a moment to carefully examine and admire the refined craftsmanship of the traditional arts in the temple.

For more pictures, please click《Divinely Inspired Craftsmanship: Skills Revealed in Mazu Temples》