Pickling fresh fruits eliminates the sour taste of the peel, softens the fruit inside, and has a preservative effect.

In the Taiwan of 40 to 50 years ago, the best-selling summertime treat was “four fruit ice,” which was made by taking a big bowl of shaved ice and covering it with a compote typically consisting of shredded papaya, candied plums and dried carambola. Old folks one and all associate this treat with happy memories. Taiwan produces fruits in huge quantities and bewildering variety. Farmers in times past found outlets for their big fruit harvests by pickling the fruit in sugar and salt, thus extending their shelf life. Some such fruit products, like green mango, became very popular snack items.

Candied fruit in Taiwan is produced principally in Changhua County’s Baiguo Mountain, Tainan City’s Anping District, and Yilan County’s Jiaoxi Township. Candied fruits these days are made in factories, but some candied fruit makers have been in business for over a century, and the rich flavors of their products show through in the histories of these firms.

Four-fruit appetizer

Huang Wan-ling, a gourmet writer and vigorous promoter of Taiwanese cuisine who is known for her lavish “rich folk’s” banquets, starts off the banquets with a four-item “welcoming course” of candied fruits that call to mind the old-time flavors of yesteryear. Huang emphasizes that the flavors of the four different types of candied fruit have to be mutually complementary, so choice of fruit is an exacting process. She goes with shredded papaya, candied plums, Chinese olives (Canarium album), and seedless dried plums.

“Four-fruit tea” is another special treat, made by taking candied fruits, steeping them in piping-hot water, and sprinkling a bit of plum powder over the tea in a ceramic mug. When drinking the tea, one uses the cup lid to keep from drinking in the fruit, while stirring the tea to ensure that the flavors are evenly concentrated. For Huang Wan-ling, the savory-sweet flavor is unforgettable, not to mention the pleasure, after finishing the tea, of taking out a fork and eating the candied fruits at the bottom of the mug. Says Huang: “Once the tea itself has gone bland, the fruits bring yet another type of flavor.” However, virtually no teahouses sell four-fruit tea nowadays because an indispensable ingredient, shredded papaya, is now exceedingly hard to come by.

“Four fruit ice” is an old-time summertime favorite of the Taiwanese.

Yilan’s oldest maker of candied fruits

There are now only two makers of candied fruits in Taiwan that have been around for more than a century. One of them, Lao Jan Sow, is located in Yilan City. The other, Chycutayshing, does business in Tainan. Historical records related to the history of candied fruits in Taiwan are scarce, but household registration documents dating to the Japanese colonial period show that Zhu Yingbin, the founder of Lao Jan Sow (original name: Lao Shou Tang), was an apothecary. Despite the fact that he ran a pharmacy, he also sold candied fruits that had been pickled using certain Chinese medicinal materials. When customers came in for medicines, they would pick up some candied fruits while there, and this sideline became well known over time.

Upon entering Lao Jan Sow today, one notices in the doorway a photo of an award that the shop won during the Japanese colonial period. Business is brisk. Some customers say they want to send candied fruits to Taiwanese friends who are living overseas and are no doubt missing treats from back home.

The older sister of today’s fifth-generation proprietor recalls how honeyed kumquats were made during her childhood. Fruit farmers would bring in baskets full of kumquats, which would be sorted by size and set in barrels to soak in water. The kumquats were rinsed clean using copious amounts of water, then candied in ceramic vats. Once candied, they were again rinsed before being placed to simmer in sugar water and malt syrup, and then left to drip dry. This sort of traditional production process, however, cannot keep up with today’s high demand for candied fruits, which is why Lao Jan Sow has switched to using a factory.

Honeyed kumquats, an old Yilan treat

According to a survey by the Council of Agriculture, some 90% of all kumquats in Taiwan are from Yilan County, grown primarily in the area around Jiaoxi and Yuanshan. Due to the abundant rainfall and well-drained land, the area has come to be known as “the hometown of the kumquat.”

In discussing honeyed kumquats, local cultural historian Zhuang Wensheng starts by commenting on the locations of Yilan’s kumquat sellers. Many of the shops that sell honeyed kumquats are concentrated along Zhongshan Road in Yilan City. During the Qing Dynasty, all the local shops and Chinese medicine apothecaries were located here. Zhuang recalls that when he was a child, the people at virtually every business in this area would busily process kumquats in front of their shops throughout the kumquat season (November to March). Entire streets took on an orange hue, and Zhongshan Road was once known as “kumquat street.”

With kumquats, the peel is sweet while the fruit is sour, which is why the people of Yilan used to “poke the kumquats,” i.e. they would first use an implement to squeeze out the sour juice before proceeding to candy them. During the lunar new year holidays some people would display a platter of kumquats on their dining table because the pleasingly round and plump shape calls to mind an image of good fortune and togetherness. An old saying holds that “kumquats make the year go great.”

In addition, kumquats help the lungs and moisten the throat, and Yilan is where Taiwanese Opera got its start. Some say that performers eat a few kumquats or drink a cup of kumquat tea before taking to the stage because it helps them sing better.

Kumquats are one of “the three treasures of Yilan,” and are a shared memory for local people.

Taking the natural path

The traditional method of candying fruits was time-consuming, and cannot keep up with today’s high demand. This has prompted many makers of candied fruits to use additives like sweeteners, saccharin, and preservatives. However, there is one maker in Yilan, Agrioz, that insists on using nothing other than sugar and salt, and carefully controls the indoor environment where the processing takes place.

First-generation proprietress Hong Meifang, a former instructor in food processing at the Ilan Institute of Agriculture and Technology, states that when making honeyed kumquats, if sugar and salt are added in the proper quantities and the moisture content of the fruit is well controlled, the result will be a natural preservative effect.

To help consumers get more familiar with kumquats, which rank as one of “the three treasures of Yilan,” the Agrioz Museum + Cafe allows visitors to view part of the production process, displays lots of photos of kumquat farmers, and provides guides to describe what the visitors are seeing. Hong Meifang explains: “Harvesting kumquats is very tough work. Every kumquat on a tree is at a different degree of ripeness, so they cannot be mechanically picked all at once. Farmers absolutely must pick the fruit by hand, one at a time.” There is also an area in the museum where visitors can try their hand at making kumquat jam and steeping kumquat tea. President Tsai Ing-wen once visited the museum and took part in these hands-on activities, and the government of Haiti, a diplomatic ally of Taiwan’s, once dispatched people to come to the museum and learn how to process and market kumquats.

During the Qing Dynasty, people turned up their nose at the very mention of sour kumquats, but clever people a few generations back figured out a way to candy them, thus turning them into mouth-watering treats. There are also many other kinds of candied fruits—such as dried Chinese olives flavored with licorice, and dried plums—that are quintessentially Taiwanese treats. The next time you boil up some tea, it wouldn’t hurt to heed a suggestion put forward by the gourmet writer Huang Wan-ling, who said: “Take just a sip of tea and a bite of candied fruit, and you’ll understand the savory sweetness and tartness that we in Taiwan remember as the old-time flavor of traditional treats.”

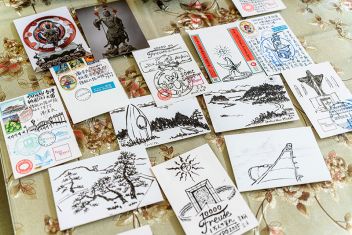

For more pictures, please click《Old-Time Treats, Old-Time Flavors》