Jieyuanpin such as the keychain and badge attached to this man’s backpack are special features of the Baishatun Mazu Pilgrimage.

As crowds of devotees on foot follow the pilgrimage of the goddess Mazu through streets and lanes, often for 100 kilometers or more, there are always cases of exhaustion or the urgent need for a bathroom along the way. Fortunately, there is help on all sides. It was out of gratitude for this precious destiny that brings people together that Jieyuanpin (“destined relationship goods”) came into being.

It’s a day when crowds of believers gather to worship and pray to the goddess Mazu at Gongtian Temple in the little town of Baishatun on the coast of Miaoli County. Some people carrying all kinds of objects step forward to report to Mazu and walk around several times in a circle amid a cloud of upwardly spiraling incense smoke. Experienced pilgrims recognize immediately that these objects are jieyuanpin—souvenirs that will be handed out along the route of the Baishatun Mazu Pilgrimage.

Baishatun: The origin of jieyuanpin

There are no specific rules for making jieyuanpin, but there are “standard operating procedures” passed down among devotees by word of mouth. When each year’s pilgrimage ends, the faithful will cast divination blocks to ask Mazu to confirm details of the jieyuanpin for the next year, including the types of goods, their materials, their quantities, and the date they will be given out.

When the jieyuanpin have been made, people bring them to the temple to report to Mazu, and then walk clockwise around the incense burner three times. Only then is their task completed.

Even if the process for making jieyuanpin is complex and time-consuming, each year a significant number of these souvenirs are handed out on the pilgrimage route. Indeed, they have even become an element of religious culture.

As for the origin of jieyuanpin, Hung Ying-fa, founder of the Platform for Taiwanese Religion and Folk Culture, believes that they began with the Baishatun Mazu Pilgrimage. He observes that jieyuanpin appeared in the procession of the Baishatun Mazu as early as 20 years ago. The quantity of these goods has grown rapidly in the past decade, reaching a peak of popularity in the post-Covid era.

There has been a three-stage evolution in the intended meaning of jieyuanpin. At first, they were simply made by devotees of the Baishatun Mazu to express thanks to the people of Beigang, the destination of her pilgrimage, for their warm welcome, says Hung.

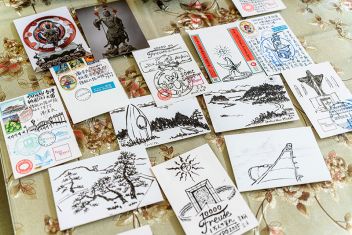

In the second stage they evolved into objects to help promote belief in Mazu. “Adherents gave jieyuanpin to people not taking part in the pilgrimage so that more would come to know about faith in Mazu.” Hung states that it was at this stage that jieyuanpin began to take on the form of cultural and creative products such as postcards and keychains, making pilgrimage culture more diverse.

In recent years these goods have gradually entered a third stage, that of individual style. He observes that in recent years various new behaviors have become noticeable among pilgrims: There are some who wear placards around their necks explaining their reasons for joining the pilgrimage, while others openly declare that they are passing out jieyuanpin to repay Mazu for her benevolence. The pilgrimage has evolved from the simple religious ritual of the past into a channel through which devotees express their individual stories and character to other people.

Hung Ying-fa adds that jieyuanpin are not exclusive to Taiwan. On “camino” pilgrimages in the West, Protestants give out crucifixes and Catholics pass out rosary beads, which are similar in nature to the souvenirs handed out at Mazu pilgrimages in Taiwan.

Hung Ying-fa, a long-time researcher of religion and folk culture in Taiwan, says that the emergence of jieyuanpin is closely connected to the transformation of pilgrimage culture.

Relationships ordained by fate

There are a wide variety of jieyuanpin in Taiwan’s religious communities, including small clothing for deities’ statues, pilgrimage flag bags, incense ash pouches, keychains, red embroidered sashes, and stickers. Li Chih-yu, an independent scholar of Taiwan folk customs and religion who has taken part in the Baishatun Mazu Pilgrimage numerous times, tells us that besides ordinary jieyuanpin, he has also received household items such as a vegetable peeler and a set of nail clippers.

Li goes on to say that there are also believers who give out jieyuanpin based on traditional customs. For example, custom dictates that when arriving in Beigang, people should bathe before going to show their respects to Tiangong (the Jade Emperor), and therefore some people along the route pass out bathing products. Also, based on the yihuo ritual, in which burning spirit money from the deity’s mother temple is placed in a container to be transported to the daughter temple—also called “renewing the divine spirit”—a custom arose of people buying matches on arriving in Beigang, and this became the basis for some pilgrims to select matches as jieyuanpin.

Li and his wife have made their own jieyuanpin to express their gratitude for help received during previous pilgrimages. Because the couple had themselves received many such gifts along the pilgrimage routes, they began to think about what kinds of objects would be useful in daily life but were things they had not previously seen during the pilgrimages.

Ultimately, in order to forge links with the Mazu faith they opted to make hand mirrors printed with “bow shoes” (small shoes with upturned ends worn in former times by women with bound feet). Reports had stated that the heels of the shoes worn by Mazu were worn down and the uppers were shredded, possibly because of Mazu’s efforts in making pilgrimages on foot and in protecting the people.

Besides being given and received, jieyuanpin also serve to build friendship between adherents of the faith, with regifting being one of the methods by which this is achieved. Li mentions that after receiving such souvenirs, if a pilgrim then receives help from someone else, they will pass along the jieyuanpin in their possession to that person to show their gratitude and to pass on this connection of “destined relationships” to the next person.

Relationships between people and deities

“In the past, I didn’t follow any one deity in particular. But one day when I was talking with Mazu, I was gradually embraced by a feeling of warmth, and I felt, ‘Wow, Mazu is really listening to what I have to say,’” So says Chu Chu, an illustrator who has taken part in Mazu pilgrimages for more than ten years, describing her destined relationship with Mazu. Her tone of voice still carries some of that original excitement.

It was thanks to this emotional connection that Chu began to take part in Mazu pilgrimages from 2008. “At that time there was not an abundance of supplies for the Baishatun Mazu Pilgrimage, and in those days before GPS, several large-scale associations had to do their best to estimate Mazu’s route and provide food and water for everyone at specific locations.” The feelings of kindness that Chu experienced during the Baishatun Mazu Pilgrimages caused her to think of ways to show her gratitude, and she set to work making jieyuanpin.

Besides postcards and incense ash pouches, the item that has earned her the greatest attention has been her hand-illustrated cards. The Mazu she depicts is exquisitely rendered and vivid, delighting many devotees. After many years of positive word of mouth, her cards, which she gives out every year, have become much-coveted jieyuanpin among pilgrims, which has been very encouraging for her.

In 2010, she got the notion to go on her own round-the-island Mazu pilgrimage on foot, and drew and photographed Mazu statues at temples large and small around Taiwan. From this she drew the inspiration for new works.

In 2019, Chu’s Studio came out with a book of short text passages accompanied by images of Mazu statues from numerous temples. Then in 2020 they began to sell Mazu calendars. Chu says that in fact there are many Mazu calendars out there, but a friend told her that the calendars on the market with photographs of real Mazu icons are a bit stressful for people to look at. Therefore, she hopes that her own hand-drawn Mazu illustrations, featuring her own personal interpretative style combined with religious value, will make Mazu more accessible to people in their daily lives.

Chu’s Studio has come out with new Mazu calendars for five straight years. Each year Chu Chu personally selects the theme and brings together drawings she has made of Mazu icons. This work has not only attracted the attention of Taiwanese, but has also found a fan in Mari Katakura, a Japanese author who has long resided in Taiwan. In her 2022 list of five must-buy Taiwanese calendars, Chu’s Mazu calendar was one of her recommendations. In the article Katakura wrote: “Just by looking at the calendar you can find a state of spiritual repose. Taiwanese often say that ‘Mazu is like a mother to all.’ If something is troubling you, perhaps a good way of dealing with it is to put your hands together in prayer and tell it to Mazu.”

As Baishatun natives, Hung Chien-hua (left), director of Gongtian Temple’s cultural team, and temple deputy director-general Lin Xingfu (right) both endeavor to ensure the preservation, continuation, and dissemination of genuine Baishatun Mazu culture.

Giving back to their hometown

Thanks to her approachable image, through word of mouth among devotees and the impact of the mass media the Baishatun Mazu has gone from being a local deity to one worshipped throughout Taiwan. This has turned the Baishatun Mazu Pilgrimage, which in the past was mainly for local people, into a major national event. Statistics show that 20 years ago 3,000-plus people took part, but in 2024 the number of registered participants has soared to 179,971, a new record.

Hung Ying-fa says that at the core of the rapid spread of faith in the Baishatun Mazu is the work of the Baishatun Field Research Workshop. Their publication Baishadun, founded in 2003, is a representative jieyuanpin.

A group of Baishatun locals, inspired by the fording of the Zhuoshui River during the 2001 pilgrimage, set up the Baishatun Field Research Workshop and in 2003 began publishing Baishadun annually. In 2015, the group was integrated into the cultural section of Gongtian Temple’s management committee, and the publication was renamed Baishatun Mazu, continuing its mission of recording activities related to the Baishatun Mazu Pilgrimage.

Hung Chien-hua, director of the temple’s cultural team, relates that each year they print 2,500 copies of Baishatun Mazu. Besides giving them away on the day when divination blocks are cast to set the date of the year’s pilgrimage, they also give out copies to lucky believers during the pilgrimage itself at random times and places. People who don’t go on the pilgrimage can read the online edition.

Lin Xingfu, deputy director-general of Gongtian Temple, tells us that because Baishatun Mazu records the events of the pilgrimage in detail, it has become an important source for academic research. Indirectly it has enabled the culture of faith in the Baishatun Mazu to become cumulative and to be transmitted, which was their initial motivation for founding the publication. “This is because culture is by its nature something that is accumulated over time.”

“When the cumulative total reaches a certain level, its impact goes beyond what we can imagine as we carry out our work in the short term,” says Lin, adding: “Rather than telling you what kind of feedback the faithful have given, it would be better to say that this accumulation of culture is in itself an enormous feedback from history.”

Each year volunteers from the cultural team move about within the procession, working to record, disseminate, and maintain the traditions of the Baishatun Mazu Pilgrimage. “We record what happens, but don’t put any spin on the facts, so the rest of the work of understanding is up to you.” This remark by Lin is the core maxim of the Gongtian Temple cultural team and represents the value that the Baishatun Mazu publication hopes to bring to devotees.

Whatever form jieyuanpin take, they are always rooted in faith. Only by understanding what underlies them can one truly understand how the pioneers of Baishatun, amidst their hardships, expressed gratitude for help received. And only then can one establish the purest “destined relationships” between people, and between people and deities.

For more pictures, please click 《Destined Relationships: The Origins, Diversity, and Meaning of Jieyuanpin》

Related Links

• 《The Past and Present of Temple Squares: Craftsmanship, Theater, Food》

• 《Transports of Devotion: Deities’ Palanquins》

• 《The Taiwanese Camino: Mazu Pilgrimages》

• 《Religion, Taiwan Style: The Polytheistic Universe of Folk Beliefs》

• 《Mad About Mazu: The Passion and Philanthropy of Pilgrimages》

• 《Divinely Inspired Craftsmanship: Skills Revealed in Mazu Temples》

• 《Mazu: Taiwan’s Leading Goddess》

• 《The Vitality of Faith in Taiwan: Chen Yi-hong’s Images of Folk Religion》